On the Works of Chris Arabadjis

The Butterfly Effect was named in the 1960’s by Edward Lorenz. He used to describe how a very simple system could yield immensely greater effects in varyingly unpredictable ways. Lorenz described the details of a tornado: its form, its velocity, path, etc., as being influenced by exceedingly minor disturbances in the weather. As the story goes, a butterfly flaps its wings, which leads to miniscule changes in its immediate environment, and then those altered conditions gradually lead to more massive fluctuations, eventually creating a tornado. Lorenz discovered the effect when he observed in the weather experiments he was repeating, that a very small change in the initial conditions of his experiments would create vastly different outcomes.

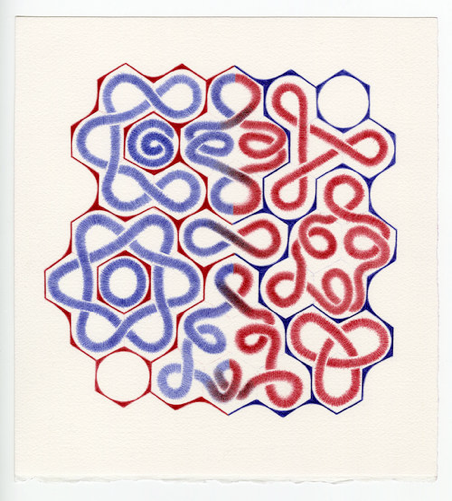

Untitled (2017-10-001), Ballpoint pen on paper, 11.5″ x 10.5″, 2017

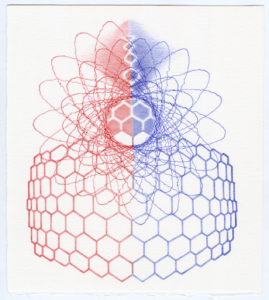

Chris Arabadjis’s fascinating drawings are like the butterfly effect wrought visual in ballpoint pen on paper. They look like mini explosions, spirals of weather graphs, wild game boards, microscopic patterns, or vast landscape formations. Their internal logic (how they’re made) recalls binary computer code, knot theory, fractal mapping, Penrose tiling, genetic mutation, and game theory. Their aesthetic complexity is arrived at by the execution and repetition of simple rules that mutate according to Chris’s own human error. He enthusiastically embraces these errors as guiding principles, and his works on the whole demonstrate how an artist can make compellingly original work from very basic materials, and within a daily routine.

Untitled (2016-08-005), Red and blue ballpoint pen on paper, 11.5″ x 10.5″, 2016

Chris makes drawings almost every day, while riding the subway to work and back. He sets up rules for himself to follow, and often begins by repeatedly drawing small modular units or by making repetitive types of marks, in systematic ways. Over time, these small marks begin to accumulate and take shape, following their predetermined rules, not unlike the way snowflakes fall on the ground and begin to gradually blanket the crevices of the landscape. In fascinatingly peculiar ways, Chris’s drawings almost build themselves. What initially might seem like a rigid way of working yields strangely beautiful and unpredictable results. When Chris stops his initial system, or changes it midway, the forms he has arrived at are completely original and would have been unimaginable at the outset – the rules themselves would never have predicted such spectacular results.

For context, in their finished states, his drawings recall the abstraction of contemporary artists such as Tom Nozkowski and James Sienna. Unlike those artists, however, Chris’s finished works maintain the integrity of their original states. Each small mark remains intact and observable (the butterfly is still flapping its wings in the tornado). The final state of the drawing does not overwhelm its parts. Rather they mimic each other, and therefore collapse time so that we can see the start and the finish of the piece simultaneously. In this way, Chris’s drawings are fundamentally fractal, but this is the fractal mark of the human hand, and in Chris’s works, the hand is extremely sensitive to the surface of the paper and the subtle shifts of color and form that develop over time. He seems to be waiting for that moment of aesthetic transformation. Chris’s drawings become aesthetically magnificent through very humble means.

Untitled (2016-12-001), Ballpoint pen on paper, 11.5″ x 10.5″, 2016

I first met Chris at Pratt Institute, where we both went to graduate school and both studied with the artist Linda Francis. During that time at Pratt, drawing was treated as a serious, autonomous medium, which differentiated Pratt from most other painting or interdisciplinary heavy graduate programs. For many of us, drawing became a vehicle through which we could engage in the world scientifically, politically, and socially. Thinking on paper was valued as integral to artistic expression and Chris’s work exemplifies this.

Untitled (2017-04-002), Ballpoint pen on paper, 11.5″ x 10.5″, 2017

Via ballpoint pen, Chris’s drawing process is almost alchemical. He achieves transformation through repetition. The micro deviations of his mark-making lead to macro shifts in overall form. In related, concrete ways, Chris’s habit of drawing daily also reflects the incremental shifts in routine. His works attempt to enter into a conversation with nature – how nature works from the inside, not what it looks like from a distance. In this way, his work recalls the chance machinations of John Cage. Chris is not interested in dictating the creation of an image according to his own tastes, but is more excited by the possibility of where a work might take him when he gives up this control to a system, process, or rule. Chris sees rules not as limitations, but as a means to transform what is known into the unfamiliar, the new. He allows his systems to grow and change over time. The shapes and forms he arrives at are unlike anyone could intentionally make if they tried. And in making them every day, as a routine, like brushing one’s teeth or showering, his work is fused with his daily movements and thoughts. His general train route might stay the same, but it’s the slightly different conditions he encounters each day (where he sits, the different bumps of the train, his mood, the slightly different time he leaves, etc.) that affect the system he sets up, and therefore creates new “errors” through which his drawings take shape. In this way, Chris’s works illustrate how the small changes that take place in and around us each day, often without our awareness, lead us to make slightly different choices that day, and eventually, like the flapping of a butterfly’s wings, more broadly shape our lives as they multiply. Ultimately, Chris’s works investigate the way natural things are made and behave, and how they evolve over time. He isn’t so much interested in the shape of the tornado but wants to enter into it, in order to find the butterfly that started it all. Who would have ever thought that ballpoint pen on paper, drawn on the shaky subway train, could reveal so much about how the universe works.

Untitled (2016-09-001), Ballpoint pen on paper, 11.5″ x 10.5″, 2016

Untitled (2017-07-002), Ballpoint pen on paper, 11.5″ x 10.5″, 2017

To view more from Chris, check out his website.